We live in an age of crises; ensuring business continuity is no longer a ‘nice to have’ for any firm. It is essential. Financial Institutions in particular are always highly sensitive to the economic disruptions brought by crisis. For their Anti-Financial Crime functions, this also means tackling changes in criminal behaviors that often occur as a result, and maintaining policies, procedures and controls that will continue to meet the standards demanded by regulators.

Therefore, compliance teams need to ensure their anti-money laundering (AML) tools are robust and flexible enough to respond to the unexpected. The first part of a solution is taking a long-term and realistic view of what impact future crises might have on their business. But it also entails taking a fresh view of alternative ways to achieve operational agility. At present, the best way to achieve that is through leveraging new technology – machine learning, Cloud computing – which allow firms to monitor risk remotely and responsively.

The spread of COVID-19 is one of the most globally disruptive public health crises since the ‘Spanish Flu’ pandemic of 1918-20. Across numerous sectors, businesses are hunkered down, seeking to weather the economic and financial storms that are following the virus. In the financial services sector, financial crime compliance teams are also facing challenges, especially rising volumes of health-related fraud.

In the medium term, there is of course reason to be optimistic. Eventually – though we cannot be sure when or how – the crisis will ease, and life will return to some form of normality. However, we will all need to learn from the COVID-19 experience, compliance teams included. The last two decades have seen multiple crises of different characters that have had major regional, and sometimes globally disruptive effects.

It seems prudent to assume, therefore, that we will continue to face what the ecologist James Lovelock calls “a rough ride to the future.” In the wake of COVID-19, therefore, rather than relax back into ‘normality’, compliance teams will need to consider potential future disruptive crises – political, military, financial, economic, technological and environmental – and how to maintain ‘business as usual’ increasingly demanding environments.

This is not necessarily bad news. One of the most welcome features of the modern world is the accelerating sophistication of technological solutions, which allow societies to operate in ‘virtual’ as opposed to ‘physical’ space. Better leveraging the potential of these new technologies can help compliance teams to maintain and reconfigure financial crime controls remotely, flexibly and consistently throughout future crisis scenarios.

After a relatively quiet period from the end of the Cold War to the turn of the millennium, history has very much returned over the last two decades. The 21st century has seen a succession of crises that have roiled particular regions, and in some cases, the globe: medical challenges such as the 2002-04 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARs) outbreak; political disorders such as the Arab Spring of 2011; security challenges such as the terrorist attacks of 9/11; and financial collapses such as the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) 2007-08. Added to this has been the disruptive impact of natural disasters such as the 2011 Tsunami.

Systemically disruptive crises have always existed: the Black Death of the 14th century, for example, killed between 75 to 200 million worldwide. However, as academics such as the Canadian scientist Vaclav Smil have pointed out, there are now more underlying threats that could cause “fatal discontinuities” to human societies than ever before. Not only do we have natural disasters and pandemics, but Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) and apocalyptic terrorism. Technological development has also made societies increasingly vulnerable to cyber-attacks and unforeseen system failures.

And, of course, we face the impacts of man-made climate change. Rising sea levels are likely to lead to increased flooding of low-lying areas across the world, along with droughts and famines, and potentially large-scale migration out of affected areas. The impact of the events arising from such dramatic change are likely to dwarf what is currently happening with COVID-19.

What makes all of these threats more dangerous still is the accelerating ‘ripple effect’ caused by increasing levels of global economic and financial complexity. As the philosopher and former trader Nassim Nicholas Taleb recently explained in the New Yorker, a globalized world has created “the great danger…of…too much connectivity.” Taleb argues that as long as the world remains so tightly connected, we can expect that crises will be difficult to contain, and create ‘infections’, whether physical or digital, that “can create a rolling, widening collapse—a true black swan—in the same way that the failure of a single transformer can collapse an electricity grid.”

Any major economic or social disruption rippling out as the result of a crisis is thus likely to reshape aspects of human activity. How they do so will vary, depending on the dimensions of the crisis – the duration, depth and scope of the event in question, as well as its impact. Most crises have ‘real-world’ impacts which lead to the breakdown of normal face-to-face interactions and movements of people and goods. However, our increased dependency on networked technology also means that we could face ‘virtual’ impacts that cripple the hidden wiring of our societies. This can include everything from relatively short-lived ATM outages to large-scale ‘Denial of Service’ cyberattacks, such as those launched by Russia against Estonian institutions and banks in 2007. And of course, it is perfectly conceivable that one ‘type’ of crisis might lead to another, increasing ‘ripple’ effects more widely.

Such events are likely to have a significant impact on crime, the evolution of which has mirrored that of the global economy. Globalization has provided crime with more opportunities than before. Improved logistics and increasingly open borders have helped facilitate illicit trades in drugs, people, weapons, wildlife and other contraband, while improved financial and trade links have helped organized criminals to launder the proceeds of those crimes across borders through Trade-Based Money Laundering (TMBL), and multiple international electronic transactions, often via the accounts of offshore shell companies. This financially open world has also allowed kleptocratic elites to squirrel away corruptly gained funds in offshore tax havens, terrorist groups to proselytize and finance their campaigns, and rogue regimes to subvert international sanctions against WMD procurement.

Any ‘real-world’ crisis is likely to have a drastic short-term effect on the production, distribution and sale of illicit goods. That has been extremely clear in the recent months of the COVID-19 crisis. The major source of serious organized criminal profits, the illegal drugs market, has clearly suffered. Media reports suggest, for example, that the Mexican drug cartels have been struggling to produce methamphetamine and synthetic opioids for the US market. Production of the drugs is highly dependent on precursor chemicals, usually sourced from Asia, and there has been a general decline in trade between China, South-East Asia and the Americas. Illicit ‘retail’ markets have also struggled. In many countries, the bars, pubs and clubs often used as venues by street-level dealers are now closed, and it’s become more difficult to conduct their trade on what are now empty streets. On 5 April 2020, CNN reported that UK heroin users were ‘stockpiling’ the drug, and the wider market for all drugs was experiencing shortages and rising prices.

Such ‘real-world’ crises can also limit options for how criminals launder the proceeds of criminal markets. For example, until recently, much of the volume trade in North American and European trade in cannabis and cocaine was conducted in hand-to-hand cash transactions, which would be ‘placed’ into the financial system either through cash-intensive front companies or through multiple payments into retail accounts, by criminal stooges known as ‘money mules’. Now, with limitations on travel and economic activity in jurisdictions under lockdown, small-businesses are largely shuttered, and many individuals are out of work or furloughed by employers. There is less cash in circulation to be paid into the financial system overall, and it is more difficult to deposit cash into branches regardless. Cash deposits – a staple element of many money laundering schemes for organized street crimes – are thus all the more noticeable and suspicious in the current climate.

However, it is conceivable that a ‘virtual’ crisis could push in the opposite direction. A collapse of the infrastructure that underpins communications or the international financial system – whether caused by an accident, technical failure, or nefarious human intervention – could dramatically change patterns of economic behavior. So far, this kind of ‘virtual’ disruption has proved to be brief, and usually over within hours and at the most, days. Most problems have proved fixable through human intervention, and distributed computing through the Cloud has made systems more resilient overall – if one part fails, considerably redundancy remains, allowing the system as a whole to stay standing. Nonetheless, systemic failures, if unlikely, are still possible. In this event, serious organized criminal activity will likely displace back wholly into the ‘real’ world, especially with trades in both illicit, and hard to find licit goods, purchased at first via cash, and then, if cash becomes tight because banks’ payments systems have failed, through the bartering of valuable items or services. Depending on how extensive a system collapse might prove to be, such an event might make the immediate placement of cash into the financial system difficult to achieve, leading to possible criminal hoarding or increased cash smuggling to unaffected jurisdictions.

As these scenarios suggest, criminal networks are highly resilient and innovative. Depending on geographic variations and the character of the crisis in question. Some geographies will be less affected than others; for example, according to recent local media reports, the Golden Triangle in South-East Asia, which produces the world’s largest amounts of heroin, has continued to operate robustly at a regional level. A recent report by a Serbian think tank, the Belgrade Centre for Security Policy (BSCP), has also indicated that although the logistics of the delivery of drugs into Western European markets via the Balkans have struggled, the region itself is now awash with cannabis and cocaine. Criminals can always find new customers.

They can also innovate when it comes to delivery channels. According to media reports, the drug trade in ‘lockdown’ societies is coping by moving increasingly online. According to a recent report in the Financial Times, German drug dealers are increasingly using social media platforms and Instant Messaging (IM) with End-to-End Encryption (E2EE) to advertise and organize the delivery of drugs. There have also been examples in the US of drug sellers setting up websites on the internet – not just the Dark Web – and selling illegal drugs (often but not exclusively psychedelics) in the open, taking payments via cryptocurrencies.

Criminals will also find new ways to exploit the crisis at hand. For example, the ongoing Syrian Civil War has led to a major increase in the criminal transportation of illegal immigrants as well as human trafficking from the Middle East into Western Europe, while the current crisis has led to a rise in scams around fraudulent medical supplies, or the grifting of supposedly ‘charitable’ donations to support medical causes. Criminals are nimble, too, finding ways to exploit undisrupted areas of activity.

Anecdotally, the crisis also appears to be having an effect on how illicit funds are being laundered. Mules are increasingly recruited online, wittingly and unwittingly, through social media, dating sites and – as unemployment rises – jobs boards. Online ‘placement’ of funds is thus also on the rise, through increased electronic personal payments into other personal retail accounts, which have been partly obscured by a general rise in such activity for perfectly legitimate reasons – neighbors paying each other for food purchased at supermarkets, for example. Fraudulent schemes are also doubling up as money laundering schemes. In a recently reported Canadian case a supposed medical charity scammed funds ostensibly to ‘fight Coronavirus,’ and then recruited people as mules to receive and send money overseas.

What does this mean for Anti-Financial Crime Compliance teams? First and foremost, like any other part of a business, Anti-Financial Crime teams need to conduct a serious review of their assets and delivery channels, their vulnerabilities, potential and likely crisis scenarios, and the capabilities required – existing and potential – to achieve business continuity. For instance, the current crisis has made all firms reflect on the capacity of their staff to do their jobs remotely in the event they can travel to their official place of work. This is already leading many businesses, even before the end of the crisis, to look at investment in home-working technology, remote systems’ access and robust security.

For Anti-Financial Crime teams, their specific legal, regulatory and moral responsibilities are to ensure that the key pillars of the Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Counter-Financing of Terrorism (CFT) regulatory framework continue to be met by their institution:

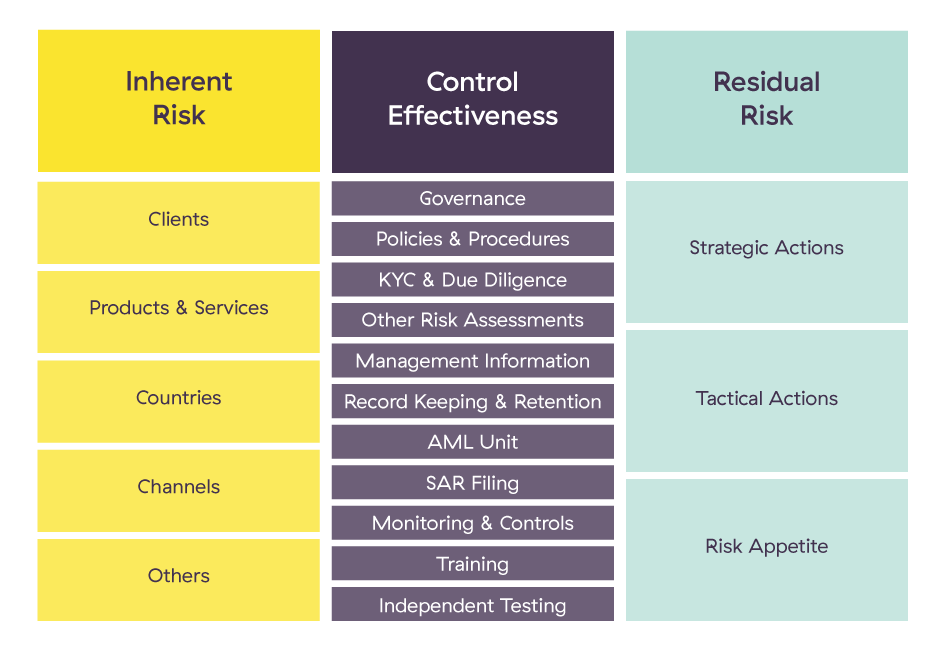

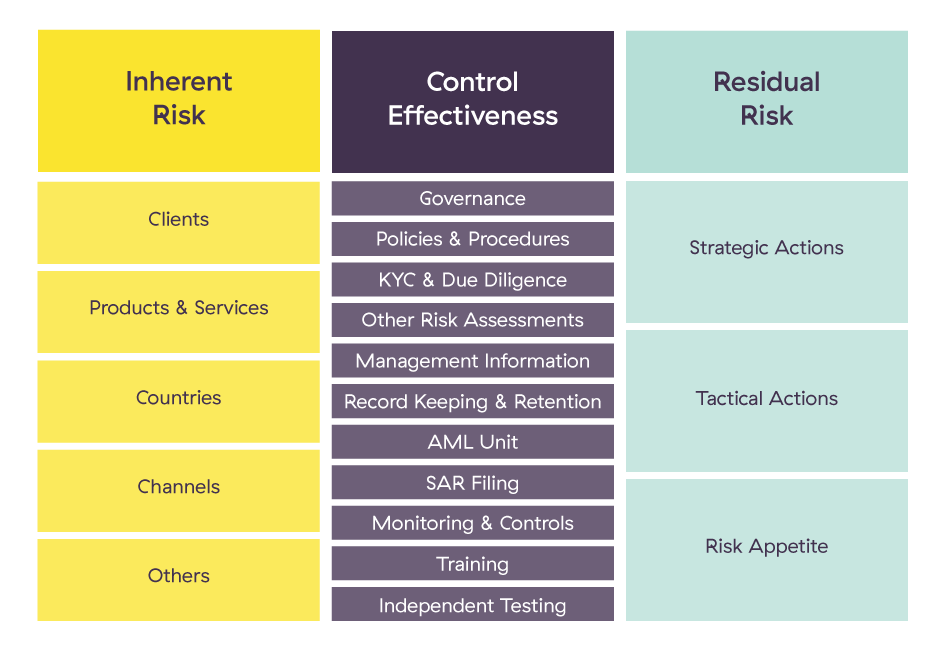

Getting those right in a crisis situation depends on institutions making a realistic appraisal of how their inherent risks might change under those circumstances, an action plan to sustain and configure effective controls, and any further actions which might need to be taken to manage any residual risks (see diagram for a classic approach to financial crime risk assessment).

The foundation of a forward-thinking approach is not to try and predict specific events, but consider ways in which likely crisis scenarios would impact the wider economy, crime, and the inherent financial crime risks faced by the business. Do we have products, delivery channels, clients, and geographies of operation that are likely to become more attractive to criminals in the event of certain types of crisis? If so, what do we need to change to protect ourselves? And can we do some of that now?

A good place to is thinking about how ‘real-world’ disruption might impact your business, especially as the majority of potential contingencies are likely to have such effects. For example, how might a future pandemic, or natural disaster such as extensive flooding, lead criminals to exploit financial services? Any type of crisis will generate fears which will be prayed on by fraudsters. Do we have effective emergency fraud warnings for customers in place that can be deployed quickly to protect customers likely to be the focus of scams? Also, the current crisis suggests that there is good reason to suspect that further social impact would further accelerate the drive towards cyber criminality, both as the source of predicate crime, and also the means for laundering proceeds. FinTech’s will need to consider the reliability of their ‘virtual’ platforms for onboarding, Customer Due Diligence (CDD) and ‘Know Your Customer’ (KYC) procedures, while legacy banks who wish to remain relevant in a largely virtual economy would have to take a more progressive view of technological innovations for AML/CFT checks. For a start, this will almost certainly mean an ever more inquisitive attitude toward paperless CDD and biometric Identification and Verification (IDV), both of which have had encouragement from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) during the current crisis.

Scenario planning also raises the issue of how easy it might be to sustain and potentially reconfigure key controls such as Screening and Transaction Monitoring when teams are forced to work remotely. Although it is difficult in advance to know exactly how financial crime risks might change, the most valuable thing to know is that systems and controls can be nimble ‘in the moment’, with the capacity to both react to changing patterns of behavior and be flexible enough to be quickly updatable. Based on anecdotal reports, there is mounting evidence that the current dramatic change in spending patterns is playing havoc with old-fashioned rules-based Transaction Monitoring systems, which take months to be reconfigured by the vendor. Again, the crisis should prompt firms to consider whether more novel and flexible solutions, based on newer techniques such as machine learning, might be more viable during future disruptions.

The support of such platforms through Cloud computing is also a vital aspect of resilience in a ‘real-world’ crisis. The nature of Cloud, which allows data to be saved across a network of linked virtual servers, can accommodate variations in processing power, data volume, and the potential loss of key ‘nodes’ in the network. Cloud is also a powerful asset in the opposite kind of crisis – a virtual breakdown – as it means that as long as relevant data is backed up to the Cloud and the network is not terminally disrupted (eg in the event of an extinction-level meteor strike), systems and data can be relatively well protected. What’s increasingly clear is that advancing technology is making it feasible to ‘do compliance’ in a range of challenging situations.

In conclusion, therefore, we believe that Anti-Financial Crime teams have to be ready before the next crisis comes, rather than waiting to extemporize at the time. The poet Rudyard Kipling once wrote in honor of those who could keep their heads while “when all about you are losing theirs,” but although it’s a great quality to have as an individual, it’s not one that should be left to chance for businesses. This means taking both a precautionary and innovative approach – being clear-eyed about what might go wrong, while also taking a long-term and radical view about how to mitigate those risks if and when they come. Business continuity planning often falls back on the tried and tested; but by being daring in preparation, there is more chance to harvest opportunities when the crisis comes. For Anti-Financial Crime teams that almost certainly means a greater push towards technological solutions that can be set up quickly, and maintained, delivered and reconfigured remotely.

Disclaimer: This is for general information only. The information presented does not constitute legal advice. ComplyAdvantage accepts no responsibility for any information contained herein and disclaims and excludes any liability in respect of the contents or for action taken based on this information.

Copyright © 2024 IVXS UK Limited (trading as ComplyAdvantage).